June 16, 2020

Indian Economy|Social Justice

Recovering from the Covid Epidemic

By Nitin Desai

The fiscal conservatism of the finance ministry means growth revival is going to take longer and may not be seen till late in the next fiscal year or even later.

Discussions about the Covid epidermic and the Government's policy announcements are shifting from how best to manage the epidermic to the most appropriate strategy for the recovery process from the social and economic havoc created by the epidemic. The stated goal is to stimulate the economy so that the growth process restarts by the the second quarter of this financial year and accelerates in the first half of the next financial year.

The Government has announced a Rs. 20 trillion package for stimulating an economic recovery and providing some relief and rehabilitation to those most badly affected. Judging by the content of the package it would appear that the government is counting largely on the stimulation of investment by easier credit availability to stimulate growth. At the sectoral level the principal initiative is a reform package for agriculture which will have its impact only over the medium and long term. It also includes initiatives , like the liberalisation of FDI in defence production and easier private participation in the space programme, which are frankly quite irrelevant to the present context The direct fiscal stimulus, in the form of additional income disposable income in the hands of households is barely 10% of the package, which amounts to about 1% of GDP. This is seriously short of the 3-5% stimulus that most economic commentators have suggested.

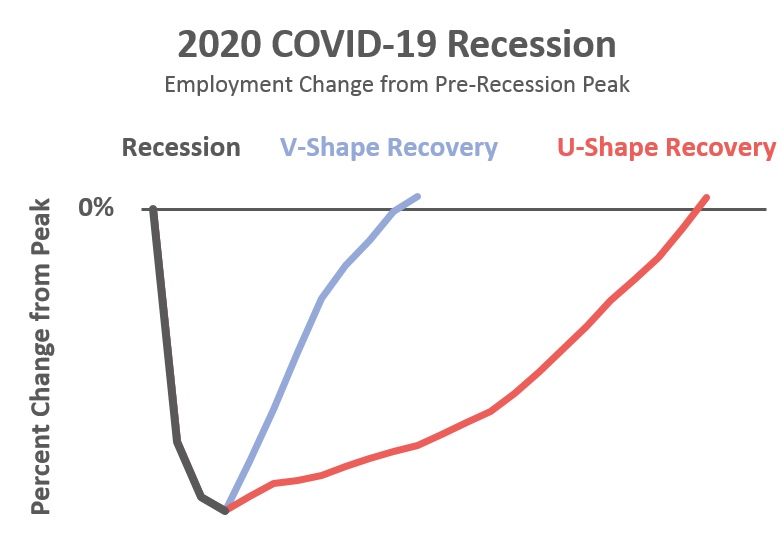

Demand has fallen drastically in the first quarter of this financial year and we may see a huge drop in the GDP when the CSO's estimates come out at the end of August 2020. The bulk of this fall will have been felt in household disposable incomes, particularly in migrant and casual labour dependent households. A 1% of GDO stimulus will do little to correct this. Without the demand stimulus easing of credit availability will not by itself revive investment and growth. The fiscal conservatism of the Finance Ministry means that the growth revival is going to take longer and may not be seen till late in the next fiscal year or even later.

The second point that one has to note is that there is no sharp distinction between the policy phase where the focus is on managing the epidemic and where the focus shifts to economic revival. The Covid epidermic is not going to go away all that quickly, as the continuing rise in the daily case increases indicates, and we will have to have a public health strategy to cope with the crisis maybe for another year or more. What is needed is aggressive testing as was done in Dharavi, which is doing well in controlling the epidemic, where one of the persons involved stated correctly"The only option then was to chase the virus rather than wait for the cases to come. To work proactively, rather than reactively." In fact one could argue that the two concerns should be connected and we should look for synergies between the task of epidemic management and economic and social recovery. The primary focus of the first phase of recovery should be on strengthening of health care and measures to provide relief and rehabilitation to migrant workers and others badly affected by the lockdown.

Consider the situation where the crisis had arisen because of a catastrophic country-wide drought that had decimated agricultural production. Clearly the recovery would begin by measures to restore agriculture and farm and labour incomes. The same logic holds now and the focus of public spending in the first recovery phase should be on strengthening public health care facilities. According to the National Health Profile 2019 budgeted public spending on health was just 1.17 per cent of the GDP in 2016-17. But this is the budgeted figure. Focusing on available data on actual spending India's public health expenditure is under 1% of GDP. In comparison, nations classified as Lower Income Countries by the World Bank spent 1.57%of their GDP on health that year. India’s public expenditure on health is way lower than the average expenditure by countries clubbed as among the "poorest". We are committed to raising this proportion to 2.5% of GDP by 2025. Surely it makes more sense to do this now rather than after the Covid epidermic.

Inadequate public spending is not the only barrier to better delivery of public health services particularly at the last mile which reaches out to households. The limited availability of medical personnel and inadequate accountability for delivery of results is a major reason for the poor state of public health services. Mobile medical facilities, telemedicine, better training for local health workers, can help to address the personnel shortage. As for accountability give priority to health workers who have performed well on defined delivery indicators when it comes to choice of postings. Of course this will require ministers in state capitals and local politicians to surrender their powers of patronage and that may be difficult!

The other area which requires urgent attention in the first recovery phase is the policy framework for migrant labour. A recent policy brief by the National Institute for Advanced Studies has suggested several initiatives.[1] These include hostels for circular migrants, providing them assured access to public health facilities and public distribution despite their lack of domicile proof, low cost train transport, flexible training and talent scouting and better rural-urban employment information networks.

It is true that this focus on healthcare and migrant workers in the primary recovery phase may not be sufficient to generate the stimulus required broadly in the economy as a whole. There will be some spin offs. Improved healthcare will be beneficial for productivity as was seen in the clear positive productivity impact of malaria eradication. But this benefit will manifest itself only over the medium term. Improvements in the policy arrangements for migrant workers, which may be effected only in the medium term, will relieve labour shortages in the West and the South and help to revive growth. Hence the primary recovery phase has to include more direct measures to relieve agricultural distress and to help MSMEs, particularly those that face the threat of close down or bankruptcy.

Ideally, the Government should present a revised budget for this fiscal year that focuses clearly on these three or four areas and provides resources and clear policy guidelines for the relief and rehabilitation process. If they do this sensibly avoiding public relations oriented flourishes, the rest of the economy will revive and the growth momentum will pick up in about a years time.

[1] NIAS Policy Brief: A Strategy for Migrant Workers by Narendra Pani, NIAS/SSc/IHD/U/PB/10 /2020, National Institute for Advanced Studies, Bengaluru